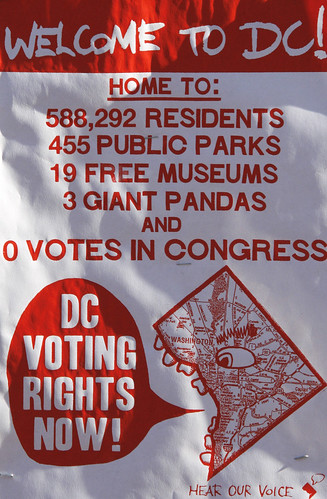

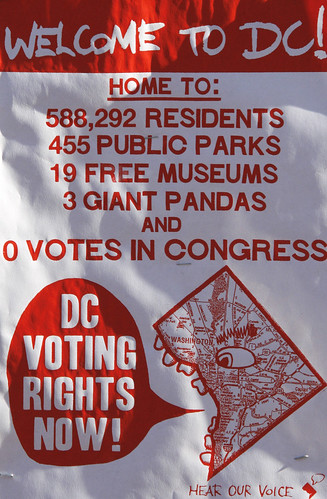

DC Voting Rights

Government Funding

Image by dbking

Source: Wikipedia…

Voting rights of citizens in the District of Columbia differ from those of United States citizens in each of the 50 states. D.C. residents do not have voting representation in the United States Congress. Instead, they are represented in the House of Representatives by a non-voting delegate who may sit on committees, participate in debate and introduce legislation, but cannot vote on the House floor. D.C. has no representation in the United States Senate.

The United States Constitution grants Congressional voting representation to residents of the states, which the District is not. The District is a federal territory ultimately under the complete authority of Congress. The lack of representation in Congress for residents of the U.S. capital has been an issue since the foundation of the federal district. Numerous proposals have been introduced to remedy this situation including legislation and constitutional amendments to grant D.C. residents voting representation, returning the District to the state of Maryland and making the District of Columbia into a new state. All proposals have been met with political or constitutional challenges; therefore, there has been no change in the District’s representation in the Congress.

The "District Clause" in Article I, Section 8, Clause 17 of the U.S. Constitution states:

[The Congress shall have Power] To exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten miles square) as may, by cession of particular states, and the acceptance of Congress, become the seat of the government of the United States.

The land on which the District is formed was ceded by the state of Maryland in 1790 following the passage of the Residence Act. The Congress did not officially move to the new federal capital until 1800. Shortly thereafter, the Congress passed the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801 and incorporated the new federal District under its sole authority as permitted by the District Clause. Since the District of Columbia was no longer part of any state, the District’s residents lost voting representation.

Residents of Washington, D.C. were also originally barred from voting for the President of the United States. This changed after the passage of the Twenty-third Amendment in 1961, which grants the District three votes in the Electoral College. This right has been exercised by D.C. citizens since the Presidential election of 1964.

The District of Columbia Home Rule Act of 1973 devolved certain Congressional powers over the District to a local government administered by an elected mayor, currently Adrian Fenty, and the thirteen-member Council of the District of Columbia. However, Congress retains the right to review and overturn laws created by the city council and intervene in local affairs. Each of the city’s eight wards elects a single member of the council and five members, including the chairman, are elected at large.

In 1980, District voters approved the call of a constitutional convention to draft a proposed state constitution, just as U.S. territories had done prior to their admission as states. The proposed constitution was ratified by District voters in 1982 for a new state to be called "New Columbia". However, the necessary authorization from the Congress has never been granted.

Pursuant to that proposed state constitution, the District still selects members of a "shadow" Congressional delegation, consisting of two "shadow Senators" and a "shadow Representative", to lobby the Congress to grant statehood. These positions are not officially recognized by Congress. In addition, until recently Congress forbade the spending of any District funds to lobby for voting representation or statehood.

There are multiple arguments for and against providing the District of Columbia with voting representation in the Congress.

The basic argument among advocates of voting representation for the District of Columbia is that as citizens living in the United States, the nearly 600,000 residents of Washington, D.C. should have the same right to determine how they are governed as citizens of a state. This argument has been laid forth by many legal scholars. For example, Justice Hugo Black described the right to vote as fundamental in Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964). He wrote, "No right is more precious in a free country than that of having a voice in the election of those who make the laws under which, as good citizens, we must live. Other rights, even the most basic, are illusory if the right to vote is undermined."

The Uniformed and Overseas Citizens Absentee Voting Act allows U.S. citizens to vote for the Congress from anywhere else in the world, except the District of Columbia. If a U.S. citizen were to move to the District, he would lose his ability to vote for a member of Congress. This is in contrast to citizens who have permanently left the United States, but are still permitted to vote for Congress in their home state.

The primary objection to legislative proposals to grant the District voting rights is that such action would be unconstitutional. The composition of the House of Representatives is described in Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution:

The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen every second Year by the People of the several States, and the Electors in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most numerous Branch of the State Legislature.

In addition, the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution similarly describes the election of "two Senators from each State". Opponents of D.C. voting rights point out that the District of Columbia is not a U.S. state and is therefore not currently entitled to representation under the Constitution. Proponents of voting rights claim that Article I, Section 8, Clause 17 (the District Clause), which grants to the Congress "exclusive" legislative authority over the District, also allows the Congress to pass simple legislation in order to grant D.C. voting representation in the Congress.

This argument is heavily debated on each side and opinions of the Supreme Court of the United States have been divided on the matter. In Hepburn v. Ellzey in 1805, the Supreme Court found that Congress could allow residents of the District access to United States federal courts in order to sue residents of other states, even though such a right is not explicitly stated in Article Three of the United States Constitution. In 1940, the Supreme Court held in National Mutual Insurance Co. v. Tidewater Transfer Co., Inc, 337 U.S. 582 (1949), that the District can be treated as a "state" for purposes of federal court jurisdiction. However, opponents of legislation to grant D.C. voting rights point out that seven of the nine Justices in Tidewater rejected the view that the District is a “state” for other constitutional purposes. Conservatives also point out that if the power of Congress to "exercise exclusive legislation" over the District is used to supersede other sections of the Constitution, then the powers granted to the Congress could potentially be unlimited.

On January 24, 2007, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) issued a report on this subject. According to the CRS, "it would appear likely that the Congress does not have authority to grant voting representation in the House of Representatives to the District."

Unlike U.S. territories such as Puerto Rico or Guam, which also have non-voting delegates, citizens of the District of Columbia are subject to all U.S. federal laws and taxes. In the financial year 2007, D.C. residents and businesses paid .4 billion in federal taxes; more than the taxes collected from 19 states and the highest federal taxes per capita. This situation has given rise to the use of the phrase "Taxation Without Representation" by those in favor of granting D.C. voting representation in the Congress. The slogan currently appears on the city’s vehicle license plates. The issue of taxation without representation in the District of Columbia is not new. For example, in Loughborough v. Blake 18 U.S. 317 (1820), the Supreme Court said:

The difference between requiring a continent, with an immense population, to submit to be taxed by a government having no common interest with it, separated from it by a vast ocean, restrained by no principle of apportionment, and associated with it by no common feelings; and permitting the representatives of the American people, under the restrictions of our constitution, to tax a part of the society…which has voluntarily relinquished the right of representation, and has adopted the whole body of Congress for its legitimate government, as is the case with the district, is too obvious not to present itself to the minds of all. Although in theory it might be more congenial to the spirit of our institutions to admit a representative from the district, it may be doubted whether, in fact, its interests would be rendered thereby the more secure; and certainly the constitution does not consider their want of a representative in Congress as exempting it from equal taxation.

Opponents of D.C. voting rights point out that Congress appropriates money directly to the D.C. government to help offset some of the city’s costs. However, proponents of a tax-centric view against D.C. representation do not apply the same logic to the 32 states that received more money from the federal government in 2005 than they paid in taxes.[18] Like the 50 states, D.C. receives federal grants for assistance programs such as Medicare, accounting for approximately 26% of the city’s total revenue. Congress also appropriates money to the District’s government to help offset some of the city’s security costs; these funds totaled million in 2007, approximately 0.5% of the District’s budget. In addition to those funds, the U.S. government provides other services. For example, the federal government operates the District’s court system, which had a budget of 2 million in 2008. Additionally, all federal law enforcement agencies, such as the U.S. Park Police, have jurisdiction in the city and help provide security. In total, the federal government provided about 33% of the District’s total revenue. On average, federal funds formed about 30% each state’s total revenues in 2007.]

Opponents of D.C. voting rights have also contended that the city is too small to warrant representation in the Senate. However, proponents of voting rights point out that Wyoming has a smaller population than the District, yet has the same number of Senators as California, the most populous state. Additionally, opponents argue that District residents choose to live in the city and are therefore fully aware of the political situation in the capital; voting rights advocates, however, claim that the majority of Washingtonians are in fact native residents. Conservatives in the United States have also made the case that the District of Columbia should not receive voting representation in the Congress because the city government is dominated by the Democratic Party and any new Representatives or Senators would likely be Democrats as well, potentially shifting the balance of power in the Congress.

There is evidence of nationwide approval for DC voting rights; various polls indicate that 61 to 82% of Americans believe that D.C. should have voting representation in Congress. Advocates for D.C. voting rights have proposed several, competing reforms to increase the District’s representation in the Congress. These proposals generally involve either treating D.C. more like a state or allowing the state of Maryland take back the land it ceded to form the District.

A number of bills have been introduced in Congress to grant the District of Columbia voting representation in one or both houses of Congress. As detailed above, the primary issue with all legislative proposals is whether the Congress has the constitutional authority to grant the District voting representation. Members of Congress in support of the bills claim that constitutional concerns should not prohibit the legislation’s passage, but rather should be left to the courts. A secondary criticism of a legislative remedy is that any law granting representation to the District could be undone in the future. Additionally, recent legislative proposals deal with granting representation in the House of Representatives only, which would still leave the issue of Senate representation for District residents unresolved. Thus far, no bill granting the District voting representation has successfully passed both houses of Congress. A summary of proposed legislation is provided below:

The "No Taxation Without Representation Act of 2003" (H.R. 1285, S. 617) would have treated D.C. as if it were a state for the purposes of voting representation in the Congress, including the addition of two new senators. The bill never made it out of committee.

The "District of Columbia Fair and Equal House Voting Rights Act of 2006" (H.R. 5388) would have granted the District of Columbia voting representation in the House of Representatives only. The bill never made it out of committee.

The "District of Columbia Fair and Equal House Voting Rights Act of 2007" (H.R. 328) was the first to propose granting the District of Columbia voting representation in the House of Representatives while also temporarily adding an extra seat to Republican-leaning Utah by increasing the membership of the House by two. The addition of an extra seat from Utah was meant to entice conservative lawmakers into voting for the bill by balancing the addition of a likely-Democratic representative from the District. The bill did not make it out of committee.

The "District of Columbia House Voting Rights Act of 2007" (H.R. 1433) was essentially the same bill as H.R. 328 introduced previously in the same Congress, though with some minor changes. This bill would still have added two additional seats to the House of Representatives, one for the District of Columbia and a second for Utah. The bill passed two committee hearings before finally being incorporated into a second bill of the same name.[31] The new bill (H.R. 1905) passed the full House of Representatives in a vote of 214 to 177. The bill was then referred to the Senate (S. 1257) where it passed in committee. However, the bill could only get 57 of the 60 votes needed to break a Republican filibuster and failed on the floor of the Senate.

] Following the defeated 2007 bill, voting rights advocates were hopeful that Democratic Party gains in both the House of Representatives and the Senate during the November 2008 elections would help pass the bill during the 111th Congress. Barack Obama, a Senate co-sponsor of the 2007 bill, said, during his presidential campaign, that he would sign such a bill if it was passed by the Congress while he was President.

On January 6, 2009, Senators Orrin Hatch of Utah and Joe Lieberman of Connecticut in the Senate, and D.C. Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton in the House, introduced the District of Columbia House Voting Rights Act of 2009. This bill is substantially similar to its 2007 version.

Given the potential constitutional problems with legislation granting the District voting representation in the Congress, scholars have proposed that amending the U.S. Constitution would be the appropriate manner to grant D.C. full representation. The last attempt at the amendment process was the District of Columbia Voting Rights Amendment, proposed by the Congress in 1978. This proposed Amendment would have required that the District of Columbia be "treated as though it were a State" in regards to congressional representation, the electoral college (to a greater extent than under the Twenty-third Amendment) and the constitutional amendment process. This proposed Amendment would not have made the District of Columbia a state and had to be ratified within seven years in order to be ratified. The Amendment expired in 1985 when it was ratified by only 16 states, short of the requisite three-fourths of the states. No further actions have been taken to amend the Constitution to grant the District representation since the proposed Amendment expired. Any new proposals would have to start the amendment process over again.

The process of reuniting the District of Columbia with the state of Maryland is referred to as retrocession. The District was originally formed out of parts of both Maryland and Virginia which they had ceded to the Congress. However, Virginia’s portion was returned to that state in 1846; all the land in present-day D.C. was once part of Maryland. If both the Congress and the Maryland state legislature agreed, jurisdiction over the District of Columbia could be returned to Maryland, possibly excluding a small tract of land immediately surrounding the United States Capitol, the White House and the Supreme Court building. If the District were returned to Maryland, citizens in D.C. would gain voting representation in the Congress as residents of Maryland. The main problem with any of the proposals is that the state of Maryland does not currently want to take the District back. Further, retrocession may require a constitutional amendment as the District’s role as the seat of government is mandated by the District Clause of the U.S. Constitution. Retrocession could also alter the idea of a separate national capital as envisioned by the Founding Fathers.

A related proposal to retrocession was the "District of Columbia Voting Rights Restoration Act of 2004" (H.R. 3709), which would have treated the residents of the District as residents of Maryland for the purposes of Congressional representation. Maryland’s congressional delegation would then be apportioned accordingly to include the population of the District. Those in favor of such a plan argue that the Congress already has the necessary authority to pass such legislation without the constitutional concerns of other proposed remedies. From the foundation of the District in 1790 until the passage of the Organic Act of 1801, citizens living in D.C. continued to vote for members of Congress in Maryland or Virginia; legal scholars therefore propose that the Congress has the power to restore those voting rights while maintaining the integrity of the federal district. The proposed legislation, however, never made it out committee.

If the District were to become a state, Congressional authority over the city would be terminated and residents would have full voting representation in the Congress, including the Senate. However, there are a number of constitutional considerations with any such statehood proposal. Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution gives the Congress power to grant statehood; the House of Representatives last voted on D.C. statehood in November 1993 and the proposal was defeated by a vote of 277 to 153. Further, like the issue of retrocession, conservatives argue that statehood would violate the District Clause of the U.S. Constitution and erode the principle of a separate federal territory as the seat of government. D.C. statehood could therefore require a constitutional amendment.

Rio Hondo looks to solar energy

RIO HONDO — Like some small towns in the area, Rio Hondo is taking its first steps to use solar energy to cut down on its light bill. Officials here will use a $ 23,000 state grant to install solar panels at City Hall.

Government Funding

Read more on The Brownsville Herald

Police get grant for fingerprinting

JOHNSTOWN – The city Police Department will be receiving a $ 37,000 federal grant for electronic fingerprinting equipment – the wave of the future for fingerprinting suspects. Lt.

Government Funding

Read more on The Leader-Herald

![]() ©Copyright 1997-

©Copyright 1997-